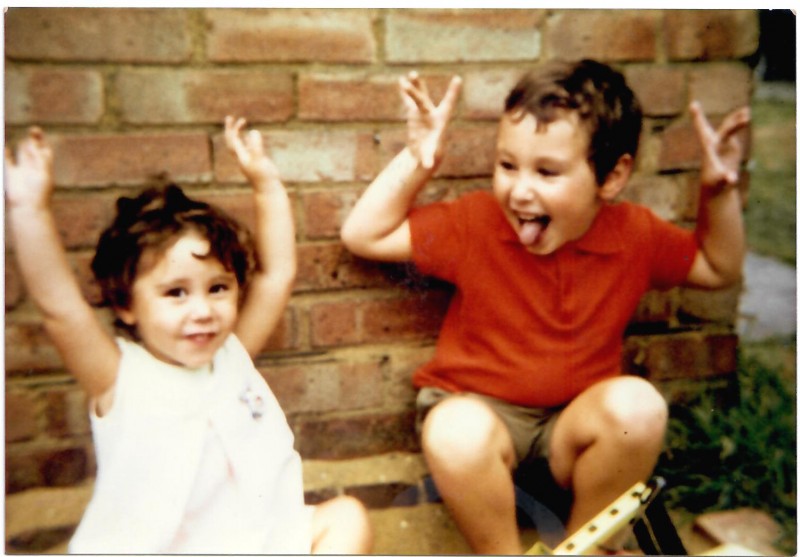

Not much compares to the pure adoration a little brother or sister heaps on their older sibling.

I remember it well.

My older brother Dave was a sci-fi enthusiast. I was determined to watch Dr Who when he watched because I wanted to be like him. It was so scary I usually ended up hiding behind the couch instead.

He was a soccer fan. I valiantly tried to keep up with him while he zoomed around the garden with a ball at his feet.

When his friend Brickie came to play at our house, I desperately attempted to join in their games. That ended when my brother laid down the law and banished me from their special boy kingdom.

Dave was nine years old when he died. I was six when I lost the childhood hero-figure who had inhabited my bedroom, my school and my entire life.

Things were already tricky in my family at that time. My mum had serious mental health issues that preceded Dave’s illness. My baby brother was born amidst the chaos of Dave’s illness. And my parents’ marriage was on the path to a difficult breakdown.

In my family, there was no space for my grief and loss, so I packed it away and denied it existed for many years until adulthood. This is an often familiar coping strategy for siblings if their own grief goes unseen and unheard.

A research study on sibling grief showed that siblings bereaved during adolescence believed their sibling’s death irrevocably changed their lives and their family members’ lives. They talked of an incomplete family and a permanent “empty space” where their sibling was.

Often, the children became more vulnerable to: particular fears about their own or family members’ mortality; survivor guilt; and the reality that life is fragile and they should take nothing for granted.

Bereaved siblings were likely to automatically assume a role of caring for, or worrying about, their parents. They often saw their relationship with the deceased sibling, and their grief, as unique and something that others would not understand.

The impact of sibling loss is one of the reasons why Red Nose counsellors work with bereaved parents, not only through their own devastating loss, but to recognise their children’s grief and loss too.

Some advice for bereaved families in discussing a loss with surviving siblings, or with siblings who come along after a bereavement:

- Be as honest as you can about what has happened

- Wherever possible, use simple, direct language, such as “he/she died”, rather than “he/she has passed away” or “has gone to a better place”. Children take language literally so they need to hear what really happened to make sense of it

- Be prepared to answer the same question more than once. Children often process information through repetition

- Meet them where they are at and provide permission for them to feel a whole range of emotions, including sadness, anger and fear

- Teach and model to children the importance of a continuing connection with the deceased. Encourage them to look at photos, share memories and even to talk directly to their siblings if they want to

- You, as a parent, carer or family member, may need professional help navigating this process - please ask for help if you need it.

Throughout my adulthood, I continue to learn about my lifelong grief for my brother.

Counselling has been invaluable in helping me to find a voice and expression for this grief.

I have learned that I am allowed to grieve too. I have explored ways to honour Dave and maintain my connection with my awesome big brother. I have learned that it is OK to display photos of us. And that our sibling relationship, as well as its loss, deserves a space to be seen and heard.

For information about Red Nose bereavement services, call our 24/7 Support Line on 1300 308 307 or visit rednosegriefandloss.org.au

Further reading and resources on supporting children through sibling bereavement

Reference: Hogan and DeSantis (1996). Basic Constructs of a Theory of Adolescent Sibling Bereavement. In Continuing Bonds (ed. Klass, Silverman and Nickman). Taylor & Francis.